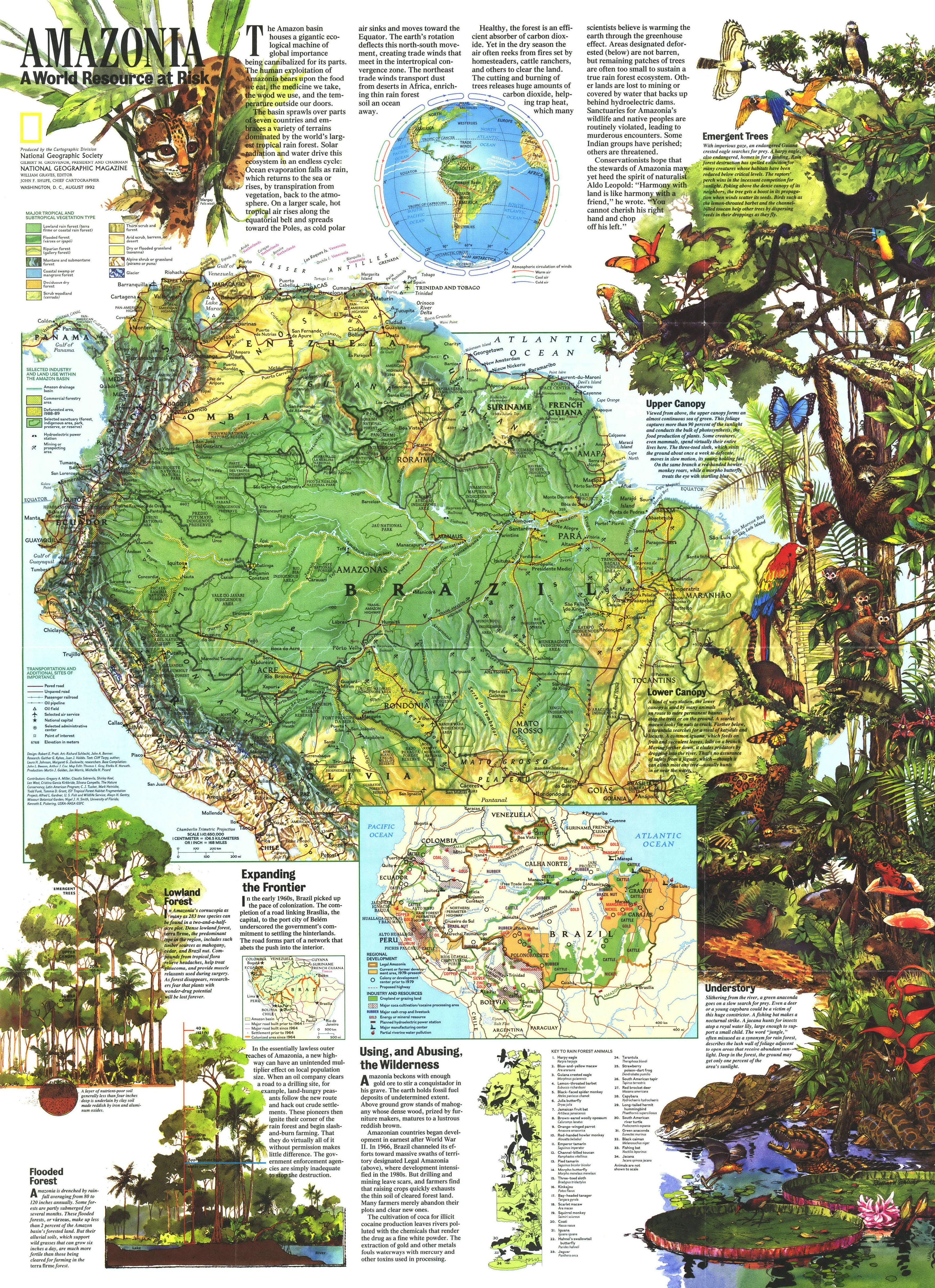

The Amazon basin houses a gigantic ecological machine of global importance being cannibalised for its parts. The human exploitation of Amazonia bears upon the food we eat, the medicine we take, the wood we use, and the temperature outside our doors.

The basin sprawls over parts of seven countries and embraces a variety of terrains dominated by the world’s largest tropical rain forest. Solar radiation and water drive this ecosystem in an endless cycle: Ocean evaporation falls as rain, which returns to the sea or rises, by transpiration from vegetation, back to the atmosphere. On a larger scale, hot tropical air rises along the equatorial belt and spreads toward the Poles, as cold polar air sinks and moves toward the Equator. The earth’s rotation deflects this north-south movement, creating trade winds that meet in the intertropical convergence zone. The northeast trade winds transport dust from deserts in Africa, enriching thin rain forest soil an ocean away.

Healthy, the forest is an efficient absorber of carbon dioxide. Yet in the dry season, the air often reeks from fires set by homesteaders, cattle ranchers, and others to clear the land. The cutting and burning of trees release huge amounts of carbon dioxide, help-_ ing trap heat, which many scientists believe is warming the earth through the greenhouse effect. Areas designated deforested (below) are not barren, but remaining patches of trees are often too small to sustain a true rain forest ecosystem. Other lands are lost to mining or covered by water that backs up behind hydroelectric dams. Sanctuaries for Amazonia’s wildlife and native peoples are routinely violated, leading to murderous encounters. Some Indian groups have perished; others are threatened.

Conservationists hope that the stewards of Amazonia may yet heed the spirit of naturalist Aldo Leopold: “Harmony with land is like harmony with a friend,” he wrote. “You cannot cherish his right hand and chop off his left.”

The basin sprawls over parts of seven countries and embraces a variety of terrains dominated by the world’s largest tropical rain forest. Solar radiation and water drive this ecosystem in an endless cycle: Ocean evaporation falls as rain, which returns to the sea or rises, by transpiration from vegetation, back to the atmosphere. On a larger scale, hot tropical air rises along the equatorial belt and spreads toward the Poles, as cold polar air sinks and moves toward the Equator. The earth’s rotation deflects this north-south movement, creating trade winds that meet in the intertropical convergence zone. The northeast trade winds transport dust from deserts in Africa, enriching thin rain forest soil an ocean away.

Healthy, the forest is an efficient absorber of carbon dioxide. Yet in the dry season, the air often reeks from fires set by homesteaders, cattle ranchers, and others to clear the land. The cutting and burning of trees release huge amounts of carbon dioxide, help-_ ing trap heat, which many scientists believe is warming the earth through the greenhouse effect. Areas designated deforested (below) are not barren, but remaining patches of trees are often too small to sustain a true rain forest ecosystem. Other lands are lost to mining or covered by water that backs up behind hydroelectric dams. Sanctuaries for Amazonia’s wildlife and native peoples are routinely violated, leading to murderous encounters. Some Indian groups have perished; others are threatened.

Conservationists hope that the stewards of Amazonia may yet heed the spirit of naturalist Aldo Leopold: “Harmony with land is like harmony with a friend,” he wrote. “You cannot cherish his right hand and chop off his left.”

This post may contain affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.